A recent study by researchers from the University of York suggests that one of Egypt’s most famous artifacts, the death mask of King Tutankhamun, might not have originally been intended for the young pharaoh. According to the team, the mask may have been crafted for a high-ranking woman, likely Tutankhamun’s stepmother, whose remains have yet to be found.

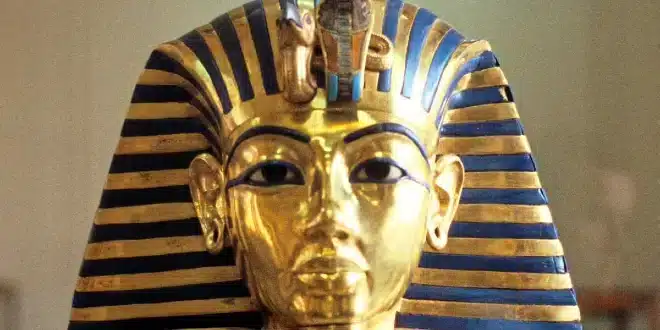

Researchers propose that Tutankhamun’s unexpected death may have prompted artisans to adapt the mask by adding his facial likeness on top of its original design. Professor Joann Fletcher noted that the mask was not made for an adult male pharaoh, explaining that an analysis revealed the face portion of the mask used a different type of gold than the rest.

This new theory emerged after re-evaluating historical records from the 1922 excavation, which mentioned body modifications that seemed unusual for traditional Egyptian practices. In one document, the focus was on a rarely noticed feature: the pierced ears on the mask, which are typically found only on the masks of children or queens. Pharaohs’ death masks did not traditionally include such piercings.

Professor Fletcher presented these findings in a recent documentary, expressing confidence that the mask was not originally created for King Tutankhamun.

The idea that the mask may have belonged to Queen Nefertiti, Tutankhamun’s stepmother, was initially proposed by Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves in 2015. Nefertiti, who married Tutankhamun’s father, Akhenaten, is still a mystery, as her tomb has never been discovered.

Tutankhamun ascended to the throne at just nine years old, ruling Egypt from 1332 to 1323 BC. The mask, found by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922 in Tutankhamun’s lavish tomb in the Valley of the Kings, served an important purpose. In ancient Egypt, such masks, typically made of gold or silver for pharaohs, were crafted to resemble the deceased and ensure a spiritual connection. Masks for commoners, by contrast, were made from simpler materials like wood or clay.